Pulling submodule’s history into the main repository

If you ever decide to somehow fold a Git submodule into the main repository, you’ll definitely end up reading this Stack Overflow answer on or that blog post by Lucas Jenß. But for whatever reason, both of these limit themselves to actions that don’t modify history. Yet if this restriction is lifted, a few more possibilities will emerge.

I’m going to present the ones that I see just in a minute, but first, let’s take a step back and see why the popular recipe doesn’t quite cut it.

The “fake merge” approach

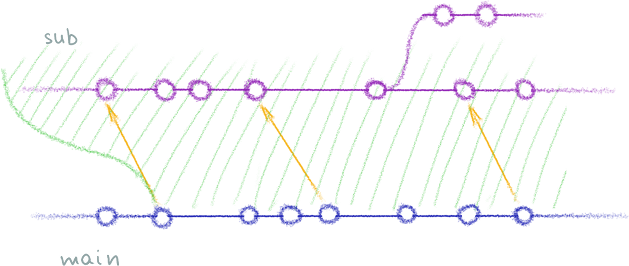

Let’s visualize our repo and its submodule like this:

The blue history at the bottom is the main repo, the purple one at the top is the submodule (with a feature branch, just to show off). The green background shows which commits of the main repo include pointers to the submodule, and the golden arrows show the pointers themselves (they’re called “gitlinks”.)

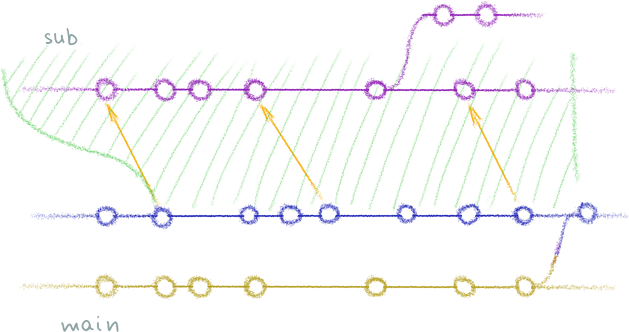

Now, if you follow the recipe from SO, you’ll end up with a history that looks like this:

At the bottom there is a Vegas-golden copy of submodule’s

history, as created by git filter-branch, and it is merged into the main

repo. The merge also removed the submodule from .gitmodules, hence the green

vertical bar on the right.

Notice how the old commits in the main history still contain gitlinks to the original submodule. That might be a problem if you plan to delete the latter, or if you’re keeping it private while publishing the main repo. If your submodule becomes inaccessible, all that old history loses a bit of value, as you are unable to fully recreate it anymore.

Can we do something about that? Well, I got a few ideas…

One repo, multiple histories

Did you know that in Darcs, branches are created by copying the repository? Well, now you do.

The reason I mention Darcs is to contrast it with Git, where a single

repository can contain any number of completely unrelated histories. They won’t

be removed by git prune as long as you have a tag or a branch pointing at

them.

We can use this to out advantage and put the submodule’s history into the main repo, and then publish the latter. This way, you’ll technically have a single repo but in reality it’ll be a repo that includes itself as a submodule. TK: insert an Inception joke here.

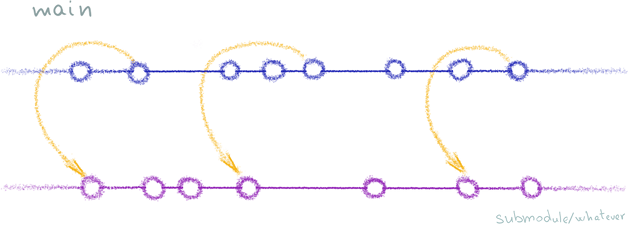

Here’s what we want to get:

Let’s get started. Pulling the submodule’s history into the main repo is a piece of cake:

$ submodule=SubmoduleName

$ git remote add --fetch sub $submodule

$ git branch submodule/$submodule sub/master

$ git remote rm subNote that “SubmoduleName” above is literally the name of the directory where the submodule currently resides. You don’t even need to hit the network to fetch it! Git is cool like that.

Now on to the scary history rewriting part:

$ git filter-branch \

--tree-filter '\

git config --file=.gitmodules \

--get submodule.${submodule}.path > /dev/null; \

if [ $? == 0 ]; then \

git config \

--file=.gitmodules \

--add submodule.${submodule}.branch \

submodule/${submodule}; \

git config \

--file=.gitmodules \

--replace-all submodule.${submodule}.url .; \

fi' \

HEADThis isn’t actually that scary, eh? git filter-branch visits every commit

reachable from HEAD and applies a filter to it, then commits a result. In our

case, we’re using a tree-filter, which means Git will perform a git checkout and run the shell script we provided. The script itself isn’t that

hard to understand either:

first, we check if submodule even exists in this particular commit.

$?contains an exit code of the last command, and in the case ofgit config, non-zero value means the key wasn’t present (for any of the reasons we don’t care about, including.gitmodulesitself being absent from the tree.)second, if the submodule is there, we edit its URL to point to current repo, and tell Git to check out the branch named

submodule/SubmoduleName. This is the that branch we created earlier.

If your main repository has more than one branch and you want to rewrite them

all, use -- --all instead of HEAD. Check out the filter-branch

manual for details on that option.

Pretending we never even had a submodule

The previous solution is reasonably simple and pretty clean, but it still

requires you to use git submodule update --init when you check out the older

commits. Can we make it look like we didn’t use submodules in the first place?

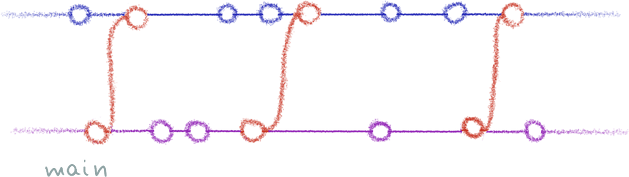

I believe that in general case, we can’t, because there’s a limit to how much a history can be tweaked without actually being changed. (I’ll expand on that in another post.) I do think that we can come pretty close, though. How does this history look to you?

The submodule here has been rewritten to reside in a subdirectory of its own, and the main history now merges from the submodule instead of pointing to it. This is pretty much what you’d see if you used a feature branch to develop something; the only catch is that the submodule branch doesn’t inherit from the main one.

To make your history look like this, you’ll have to invoke filter-branch

twice:

first you’ll rewrite the submodule’s history, moving everything under a subdirectory and noting down old and new commit IDs;

second you’ll rewrite the main repo’s history, replacing every gitlink change with a merge commit, and just checking out the relevant submodule’s tree the rest of the time.

I won’t dare to actually try and do this with filter-branch. Instead,

I started writing a tool called git-submerge which will do everything for me.

The first release rolled out this week, and

I hope to see it through to 1.0 within this year. UPD 30.07.2017: hope

abandoned. The multiple histories approach is simpler and should generally be

preferred.

Which approach is better?

First, let’s recap what we learned. The Stack Overflow recipe is simple, but you’ll have to keep your submodule around. Alternatively you can put submodule’s history into the main repo itself; that’ll look funny but it’ll work. Finally, you can do some heavy history rewriting in order to turn your submodule into a kind of an unnatural feature branch that never inherited from master, but was often merged into it.

UPD 30.07.2017: The second approach is a safe generic one. The first one can be used if your submodule is public and isn’t going anywhere. The third approach is complicated and requires good excuse to be used at all.

With that, I bid you farewell, and wish you to always guess right if the submodules are the right tool for the job. Because seriously, fixing this later is a royal pain.

Your thoughts are welcome by email

(here’s why my blog doesn’t have a comments form)